By Lia Slemons

“This is my country, Frank. I hope to live and die here.” Jujiro Wada’s friend, Frank Cotter, recorded this sentiment during the historic scouting trip he, Wada, Albert Lowell, and a small team of trail blazers made from Seward to the gold fields of Iditarod in December of 1909.

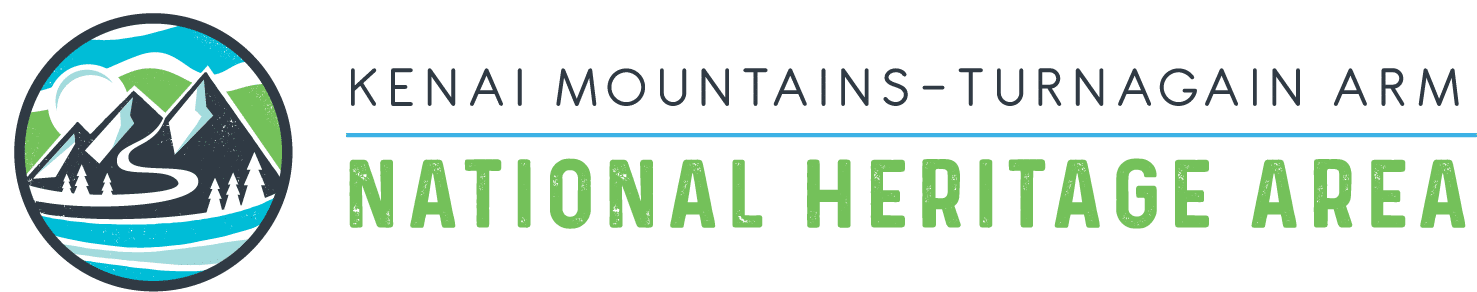

Jujiro Wada with a bear skin. He was an expert hunter.

Wada and Lowell’s team was hired by the Seward Commercial Company to string together the long-used sections of trail between Resurrection Bay and interior Alaska. Mapping and flagging a feasible route would firmly establish Seward, rather than Valdez, as the Gateway City for Alaska. On January 11, 1910, Wada was able to telegraph news of their timely trek to the Seward Chamber of Commerce from Iditarod. The historic Iditarod Trail, with Mile 0 in Seward, shaped the settlement of communities throughout the Turnagain corridor.

Wada is regaining attention in many Alaskan communities. The Kenai Mountains-Turnagain Arm National Heritage Area awarded a $24,500 grant matched with over $50,000 worth of other contributions to the Seward Iditarod Trail Blazers to create and install a Wada memorial in 2016. A bronze statue of “The Samurai Musher” commemorating Wada’s accomplishments and adventures is planned for the Obihiro/Seward sister city site on the Seward waterfront.

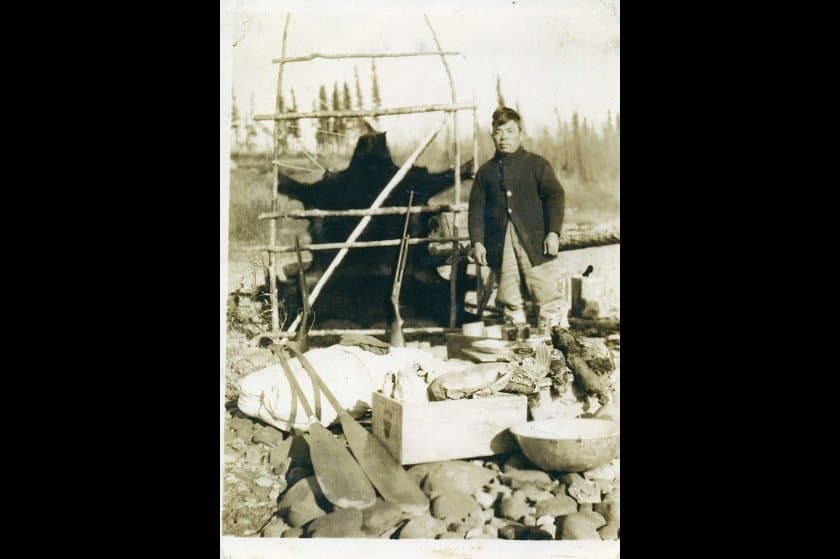

Jujiro Wada on 4th Avenue in Seward (Courtesy of the Seward Iditarod Trailblazers)

Jujiro Wada was born in the village of Komatsu-cho, of Shikoku Island, Japan, in 1875. At age 16, he left home to San Francisco, probably as a stowaway.Wada was drugged in the city and woke on an Arctic-bound whaling vessel. The captain taught his new cabin boy English.

Wada did not squander his time aboard the Balaena, which, Wada states, boasted “an exceptionally fine library … in the three years I was on the ship I read every book we had and learned to keep the ship’s log and accounts. By the end of the three years, I had a fair English education,” including the navigational skills and knowledge of biology that would serve him in years and miles to come.

Wada traveled the Yukon and the Pacific. He periodically, and briefly, returned to Japan to visit his mother. He remained close to her throughout her life, sending money, letters, and photographs.

Jujiro Wada on the Yukon River

In interior Alaska, Wada struck gold near Fairbanks in 1903. He allegedly ran to Dawson with news of the strike. Frustrated gold-seekers subsequently nearly lynched the messenger.

Nome newspapers hailed him as “King Wada, the chief of the aboriginal people of Icy Point,” apparently because of trust by local Inupiat earned by his role in negotiating a fair deal on furs with white traders.

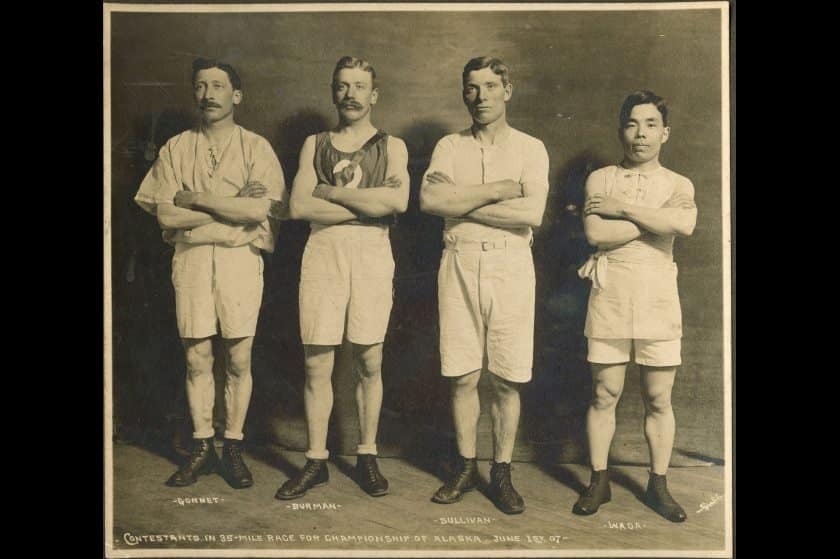

Wada’s prestige in Nome and statewide increased when he raced four ultra-marathons in 1907, winning $2800 in one 35-mile foot race.

Jujiro Wada with other marathon racers. (Courtesy of Jujiro Wada Memorial Association, Japan)

Wada returned to gold prospecting in the Yukon and developed a productive stake on the Tuluksak River. He returned $12,000 in gold to Seattle and re-equipped with materials and men, including other Japanese dog team handlers. He earned the financial backing of a variety of entrepreneurs, including E.A. McIlhenny, the Tabasco king of Louisiana. Wada met McIlhenny when he worked as a mail carrier and fur trader in Barrow.

National World War I xenophobia spread to Alaska, and in 1914 or 1915, an article in the Cordova Daily Times accused Wada of being a spy. He carried in his pack a detailed map of routes and prospecting sites.

Wada lowered his profile and continued to explore Alaska, trapping and prospecting. In 1937, though, he was in San Diego when he suffered a heart attack at age 62. He died three days later in a hospital with 53 cents in his pocket. He was buried in an unmarked grave because no acquaintance was found.

Jujiro Wada did not die in his adopted home of Alaska, but he certainly lived here. His life of mushing, prospecting, and trail blazing made an impact on routes and rushes throughout the state.

Enjoy these articles? Sign up for our monthly newsletter to be sure to see them or follow us on Facebook or Instagram. Sign up below!

Reference: Matsuura, H., Blatchford, E., Wang, S., and Nakazawa, T. (2014) Who is the samurai musher? Jujiro Wada. Studies in Science and Technology, 3(2).

Lia Slemons is a former Trails Coordinator for KMTA. She endeavors to learn the region’s trails both as an avid trail runner, recreational skier, nascent mountain biker, and expert candy-carrying mother and through their history, ancient and recent.

Lia Slemons is a former Trails Coordinator for KMTA. She endeavors to learn the region’s trails both as an avid trail runner, recreational skier, nascent mountain biker, and expert candy-carrying mother and through their history, ancient and recent.