Glacier-clad mountains rise up around Seward, a historic community nestled at the head of Resurrection Bay. Since earliest times, the “Gateway City” has been a transportation hub, a place to access Alaska’s many treasures.

The area was once a crossroads for the Unegkurmiut Eskimo, akin to the Sugpiak/Alutiiq people of Prince William Sound.

In 1792, when Alaska was a Russian colony, Alexander Baranov sailed into the bay seeking shelter from a storm. It was the Russian Sunday of the Resurrection, so Baranov named the cove Resurrection Bay. He then built a ship-building yard where he and his men constructed the schooner Phoenix. Frank and Mary Lowell settled in the area in the early 1880s. Frank eventually abandoned Mary but she and her nine children built a life gardening, raising foxes, staking gold claims, and forwarding mail from monthly steamships to the Turnagain Arm gold fields.

The city of Seward’s birthdate is August 28, 1903, the day that John Ballaine and 82 pioneers arrived to build a railroad north to Alaska’s resource-rich interior. The new community was named Seward after Secretary of State William H. Seward, who had negotiated the purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867. The first spike of the Alaska Central Railway was driven in Seward on May 4, 1904. The Iditarod Trail system, also originating in Seward, provided a winter dogsled route through the Kenai Mountains-Turnagain Arm Corridor to Alaska’s interior gold fields beginning in 1910.

Today, with a population just under 3,000, Seward continues as a transportation hub. It is the southern terminus for the Alaska Railroad and a destination of cruise ships traveling the Inside Passage. The 127-mile Seward Highway links this picturesque town with Anchorage and the interior. Buses offer daily round-trip service between Seward and Anchorage. A bus line also connects with Soldotna, Kenai, and Homer. Seward serves as a ferry stop for the Alaska Marine Highway System. Seward also has a small airport.

Home to nearly a dozen National Historic Sites, Seward is steeped in history, much of which is showcased at the Seward Museum on Third Avenue. Other historical sites include the Founder’s Monument on Ballaine Boulevard; Milepost 0 on Railway Avenue commemorating the Iditarod National Historic Trail; and the Benny Benson Memorial, a tribute to the 13-year-old Native youngster who designed the Alaska flag in 1927. Seward is also the site of the famous Fourth of July Mount Marathon race, a contest that began as a bet between two sourdoughs more than 70 years ago.

Seward boasts a scenic small boat harbor that hums with fishing activity during the summer months. A gateway to Kenai Fjords National Park, Seward is also the site of the Alaska SeaLife Center, a favorite destination for many Seward visitors.

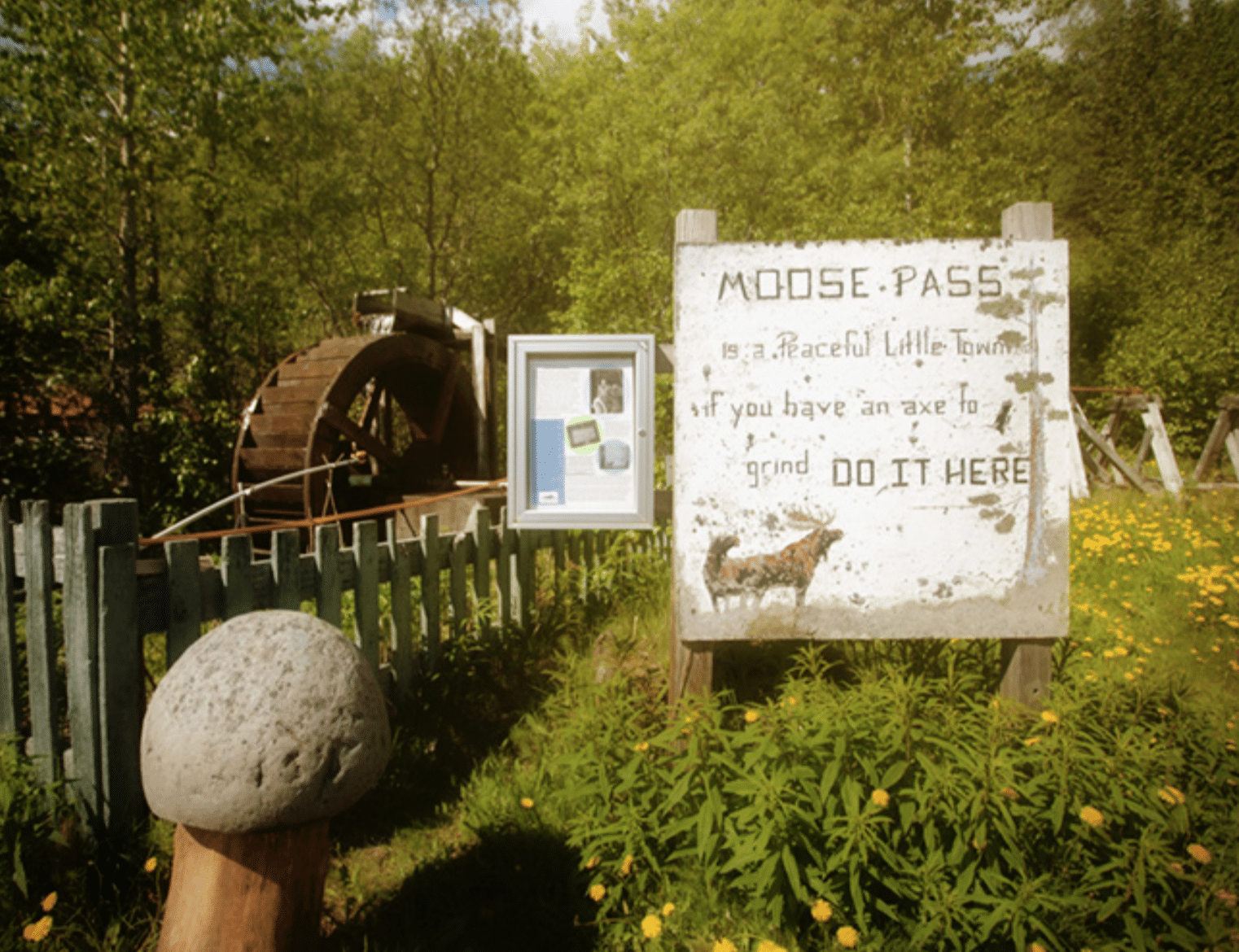

This scenic community is tucked in the Kenai Mountains along the shoreline of Upper Trail Lake. Moose Pass served as a transportation crossroads since its earliest settlers arrived by dogsled. Oscar Christensen and Mickey Natt came to the area by horse and dog team in 1909.

The log cabin and log roadhouse they built served as an inn and supply house for prospectors headed for the gold fields of the north. The original Iditarod Trail was blazed through the area in 1910 and 1911. By 1912, Moose Pass was the site of a railroad construction camp.

While many miners passed through Moose Pass to their way to other gold prospects, some stayed to develop local mines such as the Crown Point Mine, East Point Mine, and Falls Creek Mine. Silver and zinc were also mined in the area.

After Christiansen and Natt built their roadhouse, entrepreneurs built sawmills to supply timber for local construction. The railroad had a never-ending need for hemlock ties. Residents also used lumber to build homes, and miners needed wood for nearby mining operations.

The train began mail service around 1927, with sacks of letters and parcels tossed haphazardly out of the rail car. Sorting and delivering the mail was sometimes left to chance, which prompted the ire of local residents. In 1928, Leora Estes Roycroft took charge of the mail, became the first postmaster, and officially christened the community “Moose Pass.” The mail was delivered to Moose Pass by train until 1939, when service was switched to a highway carrier.

A pioneering family of the community, the Estes family provided the first electricity for the community of Moose Pass. They purchased the local grocery store, which had been in operation since the 1930s and is still in use today. The present store is part of two buildings that were joined together, with one half, part of an old roadhouse. The current counter was at one time part of the roadhouse bar. In Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula: The Road We’ve Traveled, historian Ann C. Whitmore-Painter writes, “Locals say an old-timer died at a barstool there and haunts the store today.” ‘Al’ is friendly ghost, however.

Today, the community has a population of 200 and is the site of the Annual Moose Pass Summer Solstice Festival, an event that takes place every June.

The Cooper Landing area is rich in native and pioneer history. Close to the confluence of the Russian and Kenai Rivers, Cooper Landing was once home to the Kenai Peninsula’s early people. Depressions where Native semi-subterranean houses once stood can still be seen throughout the area.

The gold rush to Cooper Creek and the northern Kenai Peninsula between 1896 and 1912 brought an influx of people, some of whom settled in Cooper Landing. In 1910, Charles Hubbard built a gold dredge downriver from the mouth of Cooper Creek on Kenai River. By that time, however, gold was beginning to dry up and miners wanting to stay in Cooper Landing had to diversify. Many became big-game guides, trappers, and fur farmers. Others subsisted on hunting, fishing, and gardening.

Families instrumental in settling the community were George Towle and his sons, Tom, Ben, and Frank; Charles and Beryl Lean, their son Clements (Nick) and Charles’ brother Jack Lean; and Duncan McGregor Little.

Cooper Landing was connected to Kenai by road in 1948 and to Anchorage in 1951. The area has been designated as a National Historic District by the National Park Service. The Cooper Landing Museum, at Milepost 48.4 of the Sterling Highway which opened in 2003, highlights local mining history and the area’s pioneers. The museum site’s four historic buildings include the Cooper Landing Post Office.

Today summer tourism and recreation fuel the area’s economy. Called the “Gem of the Kenai Peninsula,” Cooper Landing hosts the annual Festival of the Forest to celebrate the creation of the Chugach National Forest 1907.

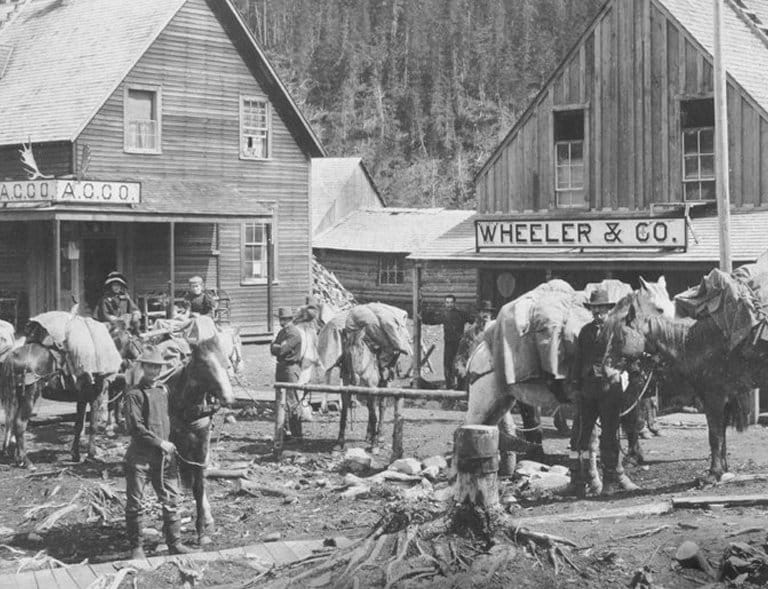

Hope and nearby Sunrise sprang up in 1895 as supply centers for miners who stampeded to the area during the Turnagain Arm Gold Rush. Business was brisk at Hope in 1898, so the Alaska Commercial Company opened a store. In 1902, miner Ed Crawford built a cabin that would, beginning in 1904, serve as Hope’s first school house.

The community came together to build a social hall in 1902, one that still serves as the town’s community center. The bustling town was reportedly home to “200 men, 2 white women, and 1 native woman.” These numbers did not include the hundreds of prospectors scattered throughout the creek drainages in the area, looking to make it rich in gold country.

The mining district was growing crowded. Most of the best claims had already been staked. So when news of the Klondike gold strike arrived, many prospectors headed for the Yukon. Miners that stayed worked first with pick and shovel and later with hydraulic mining equipment. The larger mining operations provided paying jobs but drove away many small independent miners.

By 1906, the Hope and Sunrise districts had produced more than $1 million in gold but the boom was over. Only 35-40 people wintered in Hope in 1910-1911.

Unlike Sunrise, Hope survived dwindling gold production. Resurrection Creek’s sunnier location attracted permanent settlers to take up residence in Hope rather than Sunrise, which sat in the shadow of the Kenai Mountains. Residents took up hunting and fishing and grew spectacular gardens. Some worked as guides and others worked on boats that ferried freight and people across Turnagain Arm and Cook Inlet.

Today Hope is considered the best preserved gold rush community in Southcentral Alaska. Many of the historic buildings are still in use. The Hope and Sunrise Historical and Mining Museum is now home to the Bruhn-Ray mining structures that were moved from the Canyon Creek area by the Alaska Department of Transportation. A bunkhouse, blacksmith shop, and barn, restored by the Hope and Sunrise Historical Society, give visitors a flavor of the early years. The museum also features artifact sheds with early equipment used in mining and farming. Visitors can see remnants of daily living, old newspapers, and photographs of early pioneers inside the log museum. Hope is currently home to nearly 200 residents and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as a historic district.

In 1898, Sunrise was briefly the largest city in Alaska. Today the gold rush town is just a memory, a ghost of the days when the Turnagain Arm Gold Rush brought prospectors north to seek their fortunes. Springing up along the banks of Sixmile Creek in 1895, the town was organized and platted as Sunrise City in May 1896.

Miners arrived by shallow-draft boats from Turnagain Arm and worked the Canyon, East Fork, Mills, and Lynx Creeks. A tram road built in 1899 linked the townsite with the docks and warehouses at the mouth of Sixmile Creek. During the peak of the gold rush the town’s population surged to 2,000 people.

As Sunrise grew crowded, latecomers were forced to build cabins and pitch tents on the hillsides west and east of town. A commercial ferry operation carried people by boat between the Sunrise townsite on the west bank of Sixmile Creek and the cabins on the east bank.

When the Turnagain Arm Gold Rush began to die down, Sunrise continued to be an important waypoint for the Iditarod Trail system that linked Seward with other mining camps to the north such as Knik, Iditarod, and Nome. During summers, packers carried supplies from milepost 34 of the Alaska Northern Railway over Johnson Pass to Sunrise where supplies were transferred to boats and then ferried across Cook Inlet to Knik. During the winter, supplies were transported by dog team along the railroad route to Kern – where the rails ended – and then overland across Crow Creek Pass and on to Knik. When railroad construction extended the rails to the Matanuska and Knik area in 1916, the summer traffic on the wagon road over Johnson Pass to Sunrise all but ended. This new rail link contributed to Sunrise’s decline. By the 1930s only one resident, Mike Connolly, lived in the area.

Today, all that remains of the bustling community of Sunrise is a cemetery. The Point Hope Cemetery is located off an unmarked dirt road at approximately milepost 8.5 of the Hope Highway. The cemetery was recently restored by the Hope and Sunrise Historical Society, Dennis Sammut, private owner of the old Sunrise townsite, historian Rolfe Buzzell, and other volunteers. New grave markers were replaced with replicas of the originals. Workers constructed a cedar fence around the cemetery, and the white picket fence around the “Baby Smith” gravesite was restored.

Of the 16-18 people buried at Point Comfort, five were miners killed in an avalanche on Lynx Creek during spring of 1901. Three infants are also buried there. A. W. “Jack” Morgan, in his book Memories of Old Sunrise, remembers helping dig the grave for the baby of Jack and Nellie Frost. “I believe everyone in town came down when we buried the little fellow. . . . I don’t believe there was a dry eye in the whole crowd.”

Morgan also pointed out the cemetery’s peaceful quality. “The point was covered with white snow during the winters and lovely wild flowers during the spring and summer. If I had to be buried I think it is where I would want to be.” What he failed to mention is that he and his wife had already buried an infant at the cemetery – the year before he’d helped dig a grave for the Frost child.

Whittier is a gateway to Prince William Sound and a launching point for day cruises, sea kayaking, and other adventures. Whittier is perched at the end of a 12.4-mile branch line that connects Prince William Sound with the main railroad line and the highway system along the Turnagain Arm.

The town was originally built by the U.S. Army as a deep-water port and railroad terminus to transport fuel and other supplies during World War II. A second deepwater port was built in case the port at Resurrection Bay in Seward ever fell under attack. At the height of military activity, the community of Whittier was a bustling town of more than 1,000 people. The current population is only about 182. Before 2000, the only land access to Whittier was by train. The Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel is now a combination highway and railway, allowing cars and trains to take turns traveling to Whittier.

At the head of Portage Valley, at the end of scenic Turnagain Arm, lies the Begich, Boggs Visitor Center. The center showcases the living glaciers that continue to carve the landscape and shape life in the Chugach National Forest. Built on the remnants of a terminal moraine left by Portage Glacier, the Visitor Center is staffed with Forest Service interpreters and provides programs on the historical and natural wonders of the valley. Along with interactive exhibits, the center features the award-winning film, “Voices From the Ice.”

Glacier City sprung along the banks of Glacier Creek to supply bed, food, and drink to miners and travelers in the 1890s. When James Girdwood, a well-to-do Irishman, arrived in 1900, Glacier City had one main street, a few log cabins, and a number of tent frames. Girdwood proceeded to stake several claims above Crow Creek Mine.

Known affectionately as “Colonel,” Girdwood was so well-regarded by the miners in the area that they eventually changed the name of the community from Glacier City to Girdwood. By 1917, the town had become a recreation hub for miners – of the 16 buildings then standing, five were saloons.

While mining prompted the creation of Girdwood, the development of transportation kept the community alive as the Turnagain Arm Gold Rush died down. Dog teams and their handlers stopped in Girdwood as they traveled the Iditarod Trail from Seward to the new gold fields of Iditarod and Nome. Several saw mills in the area cut ties for the tracks being laid down during the construction of the Alaska Railroad. Workers for the railroad and later road crews for the Seward Highway used Girdwood as a construction camp.

In 1954, 11 local men formed the Alyeska Ski Corporation and by 1959 the first chairlift and day lodge provided the beginnings of what would someday become an international ski resort. Constructed in 1960, the Roundhouse housed the original bull wheel for Chair One, and became home to the Alyeska ski patrol.

The land around Girdwood sank eight feet during the earthquake of 1964. The waters of Turnagain Arm rushed in and flooded the town, forcing residents to relocate two miles up the valley.

Today, Alyeska Resort, a 60-passenger aerial tramway, and world-class skiing bring visitors from all over the world to Girdwood. Even so, the community retains its small-town charm, a place rich with history and the colorful folks who call it home.

A handful of miners staked claims on Bird Creek in 1897. When the census was taken in 1900, six miners lived at Bird Creek. Bird Creek miners recovered barely enough to meet their expenses. Although mining was a bust, construction of the railroad stimulated the growth of this small settlement.

In 1909, a sawmill was moved from Glacier Creek (Girdwood) to Bird Creek to provide timber and piling that would extend the railroad from Kern Creek west along Turnagain Arm. The sawmill employed 35 men, ten horses and a donkey engine. Weekly mail service from Seward over the trail to Iditarod and Nome began in 1914. The Iditarod Trail over Crow Pass was often windy and avalanche prone. An alternate route took dog teams past Bird and on to Indian where they could more safely traverse Ship Creek Valley toward Knik. Railroad workers were stationed at a sectionhouse at Bird Creek, which served as a flag stop along the tracks until the 1950s.

The opening of the Seward Highway in 1951 provided easier access to the Bird and Indian Valleys. In the 1960s, ten couples combined their resources to purchase the Charles Pierce homestead on Bird Creek. Other people settled on the old Bystedt homestead north of the Seward Highway. In 1972, the residents of Bird, Indian, and Rainbow organized a community council, which over the years has grown to approximately 800 people.

Today the Bird Point Scenic Overlook at milepost 96.5 gives visitors a scenic view of Turnagain Arm. Interpretive panels depict the natural history of the area. Hiking and biking trails along this stretch of the Seward Highway abound. Turnouts to the west of Bird Creek/Indian allow travelers to take in the view across Turnagain Arm. From the turnouts travelers can see the cut in the mountains where Sixmile Creek drains into the Arm. The town of Sunrise once bustled with mining activity on the banks of this creek. The peak on the east side of Sixmile Creek is Mount Alpenglow. The town of Hope lays to the southwest. Bird Creek at milepost 101.2 is a popular fishing destination. The nearby Bird Creek State Recreation Site offers camping sites for fishermen and other travelers.