By Deanna Ochs

One might wonder why, until recently, there were no peaks named after her. After all, two of the tallest peaks presiding over the city of Seward, Alaska, bear the names of daughters, Alice and Eva. As the matriarch of Seward’s “first family” (1), and an essential link between two divergent worlds, Mary Forgal Lowell has certainly earned a place in history.

Born of a Russian father and Native mother in 1855, Mary Forgal seemed destined to straddle cultures. She grew up in the vital Russian fur trading station of English Bay (now Nanwalek) on the southern tip of the Kenai Peninsula. She was taught traditional subsistence practices, even while ships bearing western luxuries arrived regularly in her village. This practical knowledge, and her family connections, would serve her well at a time of rapid change in the territory. Alaska was transitioning from Russian to American rule, and white men were moving north to partake of Alaska’s bounty, particularly its access to furs. Women like Mary proved invaluable to these newcomers.

The Mary Lowell Homestead. Photo courtesy Resurrection Bay Historical Society, 21.1.4.

Like many Native and mixed-race girls of her time, Mary married into the white culture at the young age of 15. Her husband, Franklin G. Lowell, was a fur trader and entrepreneur from a prominent family in Maine. The marriage may have been voluntary or arranged. Either way, both parties were to benefit – Mary from Frank’s status as a white male from a wealthy family, and Frank from Mary’s subsistence skills and her access to Native male hunters. The couple had nine children together, some of whom would remain by Mary’s side until the end of her life.

A New Home at the Head of Resurrection Bay

Sometime between 1883 and 1884, Mary and Frank moved from bustling English Bay to the relative wilds of Resurrection Bay. Here they set up a trade station – exchanging dry goods and groceries to Native hunters for furs. They also provided transportation around the Kenai Peninsula to hunters and travelers on their schooner.

Mary Lowell’s family on the beach at Resurrection Bay. From left to right: Son William Lowell, his wife and two children, Mary, and two of her daughters, Eva and most likely, Alice. Photo courtesy Resurrection Bay Historical Society, 20.1.1.

This relatively stable existence would not last long, however. By 1892 fur trading in the area was in steep decline. Frank was called to command a more profitable trading station hundreds of miles away on the Alaska Peninsula. According to daughter Eva, however, Mary refused to leave her well-established dwellings. She stayed behind with six of her children. Despite her husband’s absence, the family seems to have fared well, hunting, fishing and cultivating a large garden. They also likely enjoyed some semblance of community. Several other Native families, possibly related to Mary, lived nearby along the coast.

The Wheels of Change Just Keep On Turning

Just 14 years after Frank’s departure, Mary Forgal Lowell witnessed another great cultural shift – this time on the very ground beneath her feet. Once again, she played a key role in the transition. Situated at the head of Resurrection Bay, her land had become coveted property. Shortly before her death in 1906, she sold her holdings to the founders of the new town of Seward. Within a few years, white settlers would be arriving on daily steamships. (2) Many were coming to help build the new railroad from Seward into interior Alaska. Mary’s quiet homestead on the shores of Resurrection Bay would soon be transformed into a bustling American town.

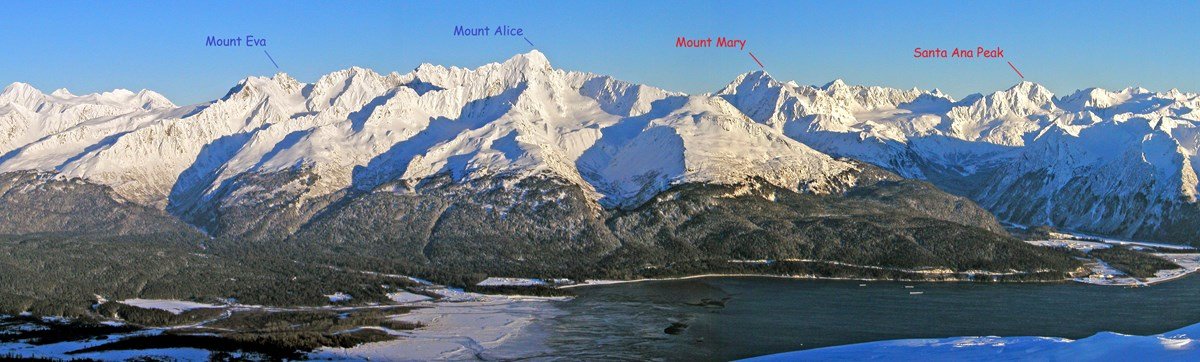

One hundred and thirteen years after her death, Mary did get that namesake mountain. On June 16, 2019 the U.S. Board on Geographic Names dubbed the peak south of Mount Alice, “Mount Mary.” Perhaps fittingly, mounts Mary, Alice and Eva stand side by side, just as the women did in life. Quietly overlooking the town of Seward, they serve as enduring reminders of the prominent role of Native and mixed-race women in Alaska’s history.

Mounts Eva, Alice and the newly christened Mount Mary tower above Resurrection Bay, just east of Seward, Alaska. Photo courtesy Harold Faust.

Enjoy these articles? Sign up below for our monthly newsletter to be sure to see them or follow us on Facebook or Instagram.

Deanna Ochs is a science communicator for the Ocean Alaska Science and Learning Center; a branch of the National Park Service, based out of Kenai Fjords National Park. She writes articles, blogs, and social media posts promoting marine science research efforts in Alaska’s coastal national parks. She lives in Seward, Alaska where she enjoys hiking, biking, skating, skiing and, yes, splashing in rain puddles. She thanks the Resurrection Bay Historical Society for its invaluable guidance in writing this article.

Deanna Ochs is a science communicator for the Ocean Alaska Science and Learning Center; a branch of the National Park Service, based out of Kenai Fjords National Park. She writes articles, blogs, and social media posts promoting marine science research efforts in Alaska’s coastal national parks. She lives in Seward, Alaska where she enjoys hiking, biking, skating, skiing and, yes, splashing in rain puddles. She thanks the Resurrection Bay Historical Society for its invaluable guidance in writing this article.

This article originally appeared on the National Park Service’s website.