By David Reamer

The Turnagain Arm’s appearance is deceptive. The water appears safe, or as safe as any other waterway. The bordering land appears solid. At low tide, the Arm even appears crossable on foot. The dominate popular perception of the Arm is of stunning vistas, whale sightings, and, admittedly, less enticing road construction. But this appearance belies its mistake-laden history. The history of the Turnagain Arm complicates its appearance and suggests a healthy measure of respect is required for old-timer and newcomer alike.

The Turnagain Arm name is itself a relic of smashed hopes. In 1778, amidst his third voyage, British explorer James Cook dreamed that the waterway was in fact a passage to an inland sea and, beyond that, Europe. Disappointed by reality, he labeled it the River Turnagain, for literally forcing the crew to “turn again.” Charles Clerke, captain of the HMS Discovery, the second ship in the expedition besides the Cook-helmed HMS Resolution, summarized British opinions. He described the Arm as “a fine spacious river, but a cursed unfortunate one to us.”

Steamer Toledo aground on May 2nd, 1906. Photo courtesy of Alaska State Library ASL-P226-600 William Norton Collection

In the twentieth century and beyond, the local secret of the Turnagain Arm was of the frequent deaths associated with the area. Simply being near the Arm was dangerous, as one little slip or push puts you at risk of a frigid death. In 1920, an avalanche struck several railroad workers on the northern shore. Two men were swept into the Arm where they drowned. In the summer of 1958, two road crew workers fell into Six Mile Creek east of Hope and were dragged into the Turnagain Arm. One body was discovered nearly three months later when it washed ashore. The other body was never recovered.

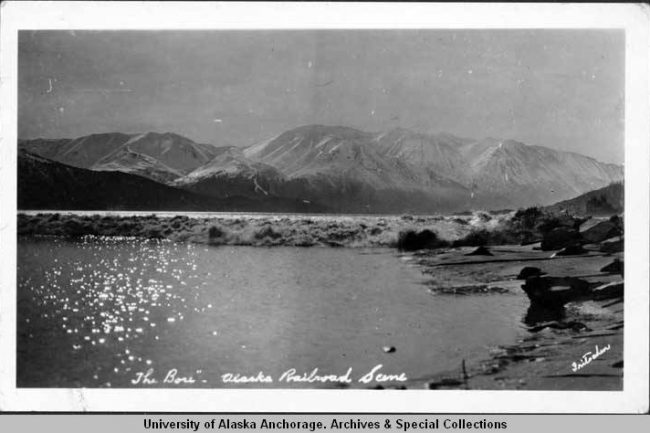

The water itself is cold and murky with the, depending on who you ask, second, third, or fourth highest tide in the world. The resultant bore tide can reach as high as ten feet, thrilling surfers and capsizing boats. Aided by frequent high winds, windsurfers have reached board speeds of 50 mph. But in 1988, experienced windsurfer Patrick Hallin was ripped from his board, swept out of the Turnagain Arm. His body was finally discovered three weeks and around ninety miles away.

The Bore Tide of Turnagain Arm Circa 1930s-1950s. Photo courtesy of the Marie Silverman papers, Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage. (HMC-0778)

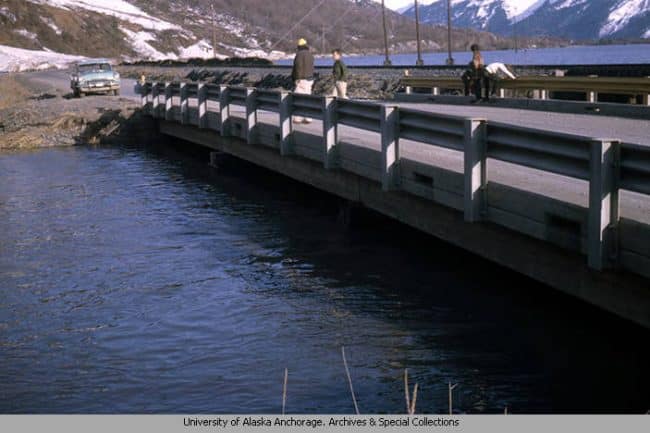

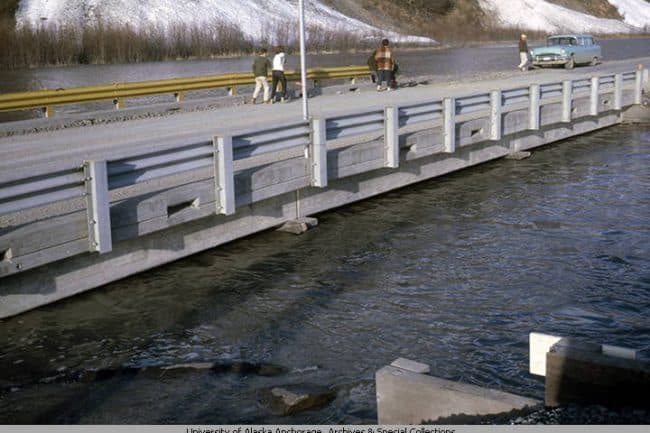

Another view of Turnagain Arm’s High Tide in 1964. Photo Courtesy of Alice and Bob Arwezon photographs, Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage. (HMC-1140)

Turnagain Arm’s High Tide in 1964. Photo Courtesy of Alice and Bob Arwezon photographs, Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage. (HMC-1140)

Many pilots over the years who have attempted emergency landings in The Turnagain Arm surely preferred a water landing over a land crash. And in many instances, they were wrong. In 1949, 26-year-old Tom Maloney crash landed a Waco biplane in the Arm a quarter mile from the shore, near Burnt Island and west of Hope. He had years of Alaska experience combined with Coast Guard service. His father worked for the Alaska Steamship Company. But he could not make the swim. His passenger survived, though haunted by the memory of Tom’s last cry for help before slipping beneath the water for the last time.

For many, the best advice regarding the Turnagain Arm and the greater Cook Inlet is to avoid them. Said one local hunter to the Anchorage Times in 1981, “Don’t get your feet in the water, don’t even get wet.” Per a representative for the State Fish and Wildlife Division, “My best advice is don’t even go out on it. There’s just not that much about Cook Inlet that’s enjoyable.” Still, the Cook Inlet roughly averages one search and rescue a week, either for a plane, boat, or swimming accident.

A last cautionary tale of the Turnagain Arm regards the glacial silt mudflats that line much of the Turnagain Arm. The small, angular grains compact around objects, such as feet, locking them into the mud. On July 15, 1988, Adeana and Jay Dickison headed for the Turnagain Arm’s eastern terminus, near Portage, for some recreational gold dredging. Only 18 years old, Adeana married Jay a month prior in Nevada before moving to Eagle River. They rode a four-wheeler dragging a trailer of equipment across the tidal flats but got stuck in the mud along Ingram Creek, about forty-five miles from Anchorage. Adeana pushed the ATV from behind but became trapped herself.

For three hours, Jay fought to free his wife. He used a dredge from their mining gear to pump the mud away. He worked one leg out, but a dredge belt slipped before he could free the other leg. Jay then ran to the highway, searching for help. Alaska State Trooper Mike Opalka was the first to arrive. He rushed across the flats to comfort the screaming and panic-stricken Adeana. By then, the icy water was up to her chest. Opalka hurried the half-mile back to the highway to guide arriving firefighters. By the time they returned, the water had reached her face.

Opalka pressed a tube removed from the mining equipment into Adeana’s mouth, but she was too hypothermic to breathe steadily, let alone hold the tube. Though nearly frozen himself, Opalka was still wrapped around her, still pulling when the water covered her. When backup arrived from Anchorage, the earlier responders were staring at the now smooth water that covered Adeana Dickison. There was nothing left to do but wait for the tide to recede, to allow them to recover her body hours later.

Turnagain Arm is stunning but perhaps best admired from the surrounding mountain peaks or a Seward Highway pull off. Be careful if you venture onto the mudflats or into the water. The best advice might be to just stay dry.

Enjoy these articles? Sign up for our monthly newsletter to be sure to see them or follow us on Facebook or Instagram. Sign up below!

David Reamer is an academic and public scholar interested in the intersections of social justice, history, and community construction. He writes weekly for the Anchorage Daily News, daily on Twitter (@ANC_historian), and has elsewhere written on a range of topics, from housing discrimination to baseball, and food insecurity to the English Gin Craze.

David Reamer is an academic and public scholar interested in the intersections of social justice, history, and community construction. He writes weekly for the Anchorage Daily News, daily on Twitter (@ANC_historian), and has elsewhere written on a range of topics, from housing discrimination to baseball, and food insecurity to the English Gin Craze.