By Dan Walker

Late Night Trail Running on Mt. Tiehacker near Seward, Alaska by Nelson Brown (Entry into the KMTA Photo Contest 2020)

Anyone who drives the Seward Highway and enters the mountains west of Portage gets the sense that they are driving into the wilderness. The forests reach down the mountain sides to the very edge of the road, lively streams tumble down rocky slopes, and lofty peaks rise above it all. It’s easy to believe that this land, most of it in Chugach National Forest, is acres and acres of pristine wilderness whose only mark by man is a ribbon of highway and belt of railroad passing through the boreal forest like a boat wake on the endless ocean. In fact, very little of the land of the KMTA corridor is untouched wilderness, and even the highest peaks visible from the highway show the mark of man.

For example, where I live on Bear Lake north of Seward, I look out at a pristine lake surrounded by towering forests of spruce and hemlock. It looks like a virgin forest, and I could easily brag that I live on the edge of untouched wilderness. For the forest reaches from tree line on Mount Tiehacker to the alder fringe of the lake where only a few houses line the south shore. Loons, and golden-eye ducks make the lake their home as do river otters and muskrats. In August brown bears wade the shallow shoreline, harvesting salmon — they take short cuts through our yard without regard to our presence–, and moose feed on lakeside willows throughout the winter. Sounds like a wilderness doesn’t it, wild animals roaming free through land unmarred by humans.

Mt. Tiehacker near Seward, AK on the Kenai Peninsula. It was named for the men who spent their winters in the woods around Bear Lake cutting ties to support the iron rail of the Alaska Railroad as it was constructed from Seward to Fairbanks over a hundred years ago. Photo courtesy of Dan Walker

Actually, nothing could be farther from the truth. Mount Tiehacker was named for the men who spent their winters in the woods around Bear Lake cutting ties to support the iron rail of the Alaska Railroad as it was constructed from Seward to Fairbanks over a hundred years ago; a railroad uses over three thousand eight foot ties per mile. That’s a lot of hemlock trees ( the preferred local wood for ties, I’m told) to be harvested along the route through what is now the KMTA corridor. But that’s only part of the story. My house is built on the site of a mill that provided kiln-dried lumber throughout southcentral Alaska until 1973. The steep shores of Bear Lake and the forest mountain slopes beyond were harvested for spruce and hemlock and floated down the lake to the mill, located at the outlet at Bear Creek. The lakeside forest is all second growth timber, forest that has been logged. In the ensuing years the forest reclaimed the land and all but a few of the trails and roads used for logging are grown over by alder and devils club.

Where the lumber mill stood, my neighbors and I had to fell acres of woods, some thirty feet tall, before we could build our homes. In less than forty years the forest had repopulated the lake site with spruce, alder and cottonwood. Looking north across the lake today, one imagines the wild country is untrammeled by man, but following the Iditarod Trail along the south and east shore one can see the old stumps with flat tops (evidence of the logger’s saw) covered with moss and hosting young saplings.

This country gets enough rain that the short summer with endless hours of sunlight make the southern coast of the Kenai Peninsula the most northern rainforest, and every summer the forest tries to take the land back from us, sprawling into our yards and driveways with willows and alders leading the way. This time of year when the bright fruit of the elderberry hangs into the driveway we call it the jungle, and we must hack and saw at the advancing cottonwood, pushki and devil’s club as the forest tries to reclaim the land.

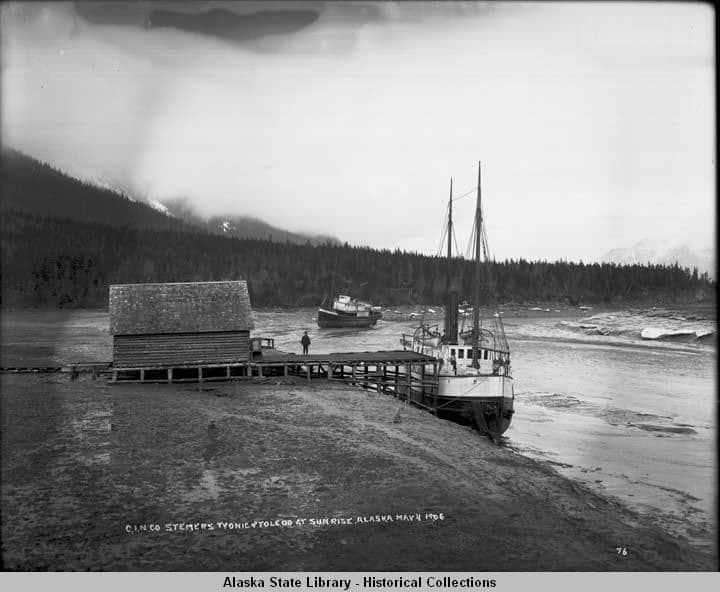

C.I.N Steamerss Tyonic and Toledo at Sunrise, Alaska in 1906. One rests on the mud and one is tied to the dock. (AK State Library P448-69, Clinton H. Betz Photo Collection) Sunrise, located near Hope, is one of the boomtowns that has been swallowed by the forest.

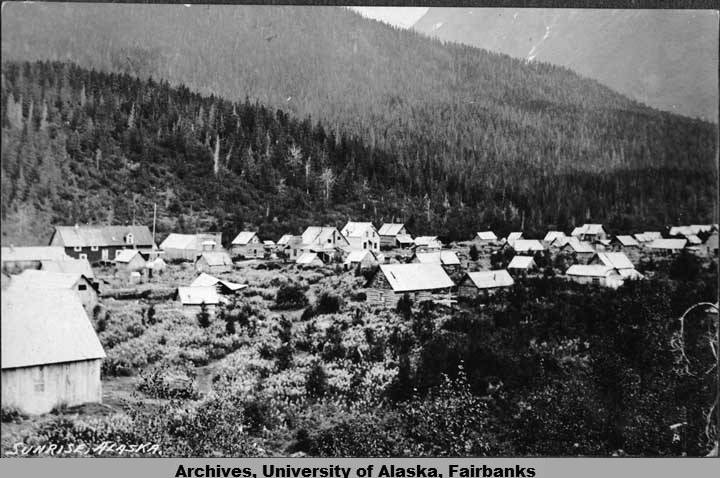

View of Sunrise, Alaska in 1913 (Reverend S. Hall Young Album UAF-2001-38-103)

This same scenario has been played out all along the KMTA corridor, whether the subterranean barbaras (house) of the First Alaskan’s along the Kenai River, the miner’s trails and excavations, or the broad swath of the tie hackers axe along the Alaska Railroad. As soon as man steps back, the forest begins to cover the scars. Whole mining camps and gold rush boomtowns like Lawing, Sunrise and Widel have been swallowed by the forest and only those who know where they are can find them. Prospectors built trails, roads and canals along the many of the hillsides in the heritage area. They show up now as straight lines of alder angling up the mountain, too straight to be natural. Above Summit Creek, for example, one can see a dramatic Z pattern on the hillside all the remains of a trail leading to test mine high on the mountain side.

Lawing Station on Kenai Lake via Alaska Railroad in July 1943. Lawing has also become a part of the past. (AK State Library – P448-69, William Norton Photo Collection)

Most of the hiking trails that crisscross the Kenai Mountains follow the mining roads and hunting trails that have gone before while other routes have been surrendered to the forest. Whether we are hiking one of these trails, fishing a favorite hot spot, or just driving the scenic KMTA corridor, we can be assured that while this land might not be wilderness, it is still wild, and it is the wildness that is the greatest resource. Instead of coming to harvest the treasures of the wilderness we have come to treasure the wildness itself.

Enjoy these articles? Sign up for our monthly newsletter to be sure to see more of them or follow us on Facebook or Instagram. Sign up below!

With over fifty years on the Kenai Peninsula, Dan is older than lots of the trees. Walker lives in Seward and after thirty-five years in education, is the president of the KMTA Board of Directors and author of Letters from Happy Valley, Memories of an Alaska Homesteader’s Son.

With over fifty years on the Kenai Peninsula, Dan is older than lots of the trees. Walker lives in Seward and after thirty-five years in education, is the president of the KMTA Board of Directors and author of Letters from Happy Valley, Memories of an Alaska Homesteader’s Son.