By Clark Fair

It is nearly impossible to pass through Cooper Landing and fail to notice craggy Cecil Rhode Mountain standing sentinel over the community near the nexus formed by the Sterling Highway, Snug Harbor Road, Bean Creek Road, and the bridge spanning the headwaters of the Kenai River. Rising to 4,405 feet just above the highway—and to nearly 4,600 feet on one of its back ridges—Cecil Rhode Mountain dominates the scenery in an area dominated by mountains and the turquoise sweep of Kenai Lake.

View from atop Cecil Rhode Mountain

The mountain is named for Cecil Rhode, a renowned former resident of Cooper Landing, a man whose wife, Helen, was renowned as a photographer; whose younger brother, Leo Rhode, was renowned as 15-year member of the Alaska State Legislature, a member of the University of Alaska Board of Regents, and a two-time mayor of Homer; and whose cousin, Clarence Rhode, was renowned for his speedy climb to the top of the territorial Game Commission and for the long mystery surrounding his death in a 1958 plane crash. (The remote crash site went undiscovered for 21 years, despite an extensive search costing more than $1million, according to Forgotten Heroes of Alaska by William Wilbanks.)

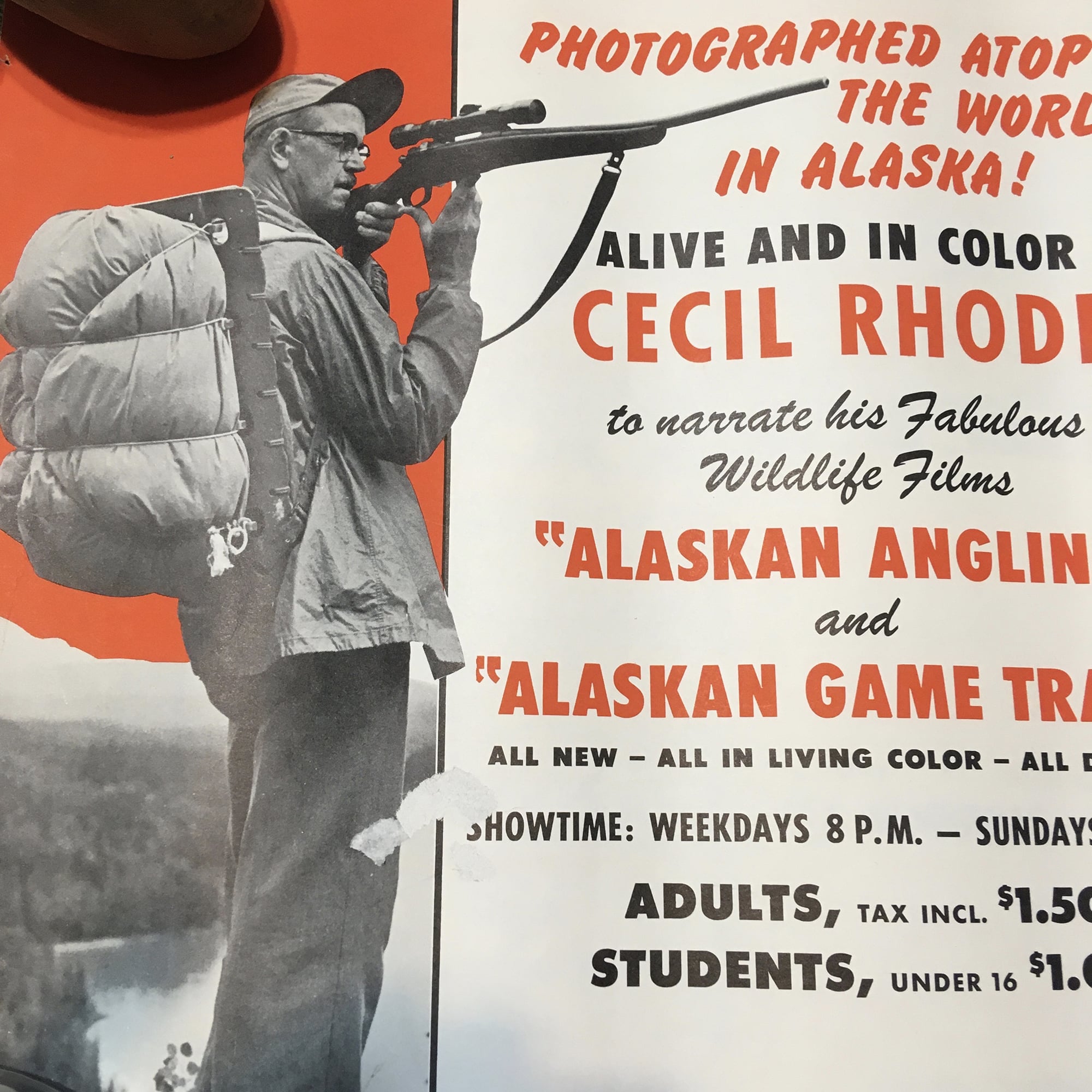

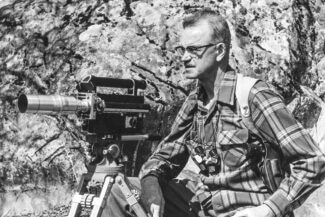

Cecil Rhode himself, who in 1937 built a cabin on a federal homesite parcel in Cooper Landing, was known primarily for his wildlife cinematography, which he turned into his full-time profession in 1946. For many years, he filmed wildlife in Alaska during the summers and then traveled to the Lower 48 during the winters to present and narrate his films.

He also worked for three years as a cinematographer for Disney Studios, and he published illustrations and articles in National Geographic, Outdoor Life and a number of other periodicals. In his later years, he was also a popular still-picture photographer.

Cecil Rhode with his filming equipment.

Rhode was born in North Dakota in 1902 and moved with his family to Oregon and then to Eureka, Kansas, where he graduated from Eureka High School. According to a 2002 article in the Eureka Herald newspaper, Rhode worked in the local Carter Jewelry store, first as a janitor and errand boy, but soon learned how to repair and build timepieces.

While panning for gold in Colorado in the early 1930s, he became enamored of prospectors’ tales of Alaska, so in 1933 Cecil and Leo headed north, intending to float the Yukon River. They arrived by steerage on a steamship into Ketchikan, where they obtained a skiff and spent the summer sailing more than 600 miles to Haines. They enjoyed themselves so much that they convinced Clarence to join them in 1935, and all three men lived out their lives in Alaska.

In fact, Cecil kept his same cabin and homesite on Kenai Lake, living there for all but the four years of U.S. involvement in World War II, when he closed the door of his home and traveled to Seattle to work in Boeing’s instrument division.

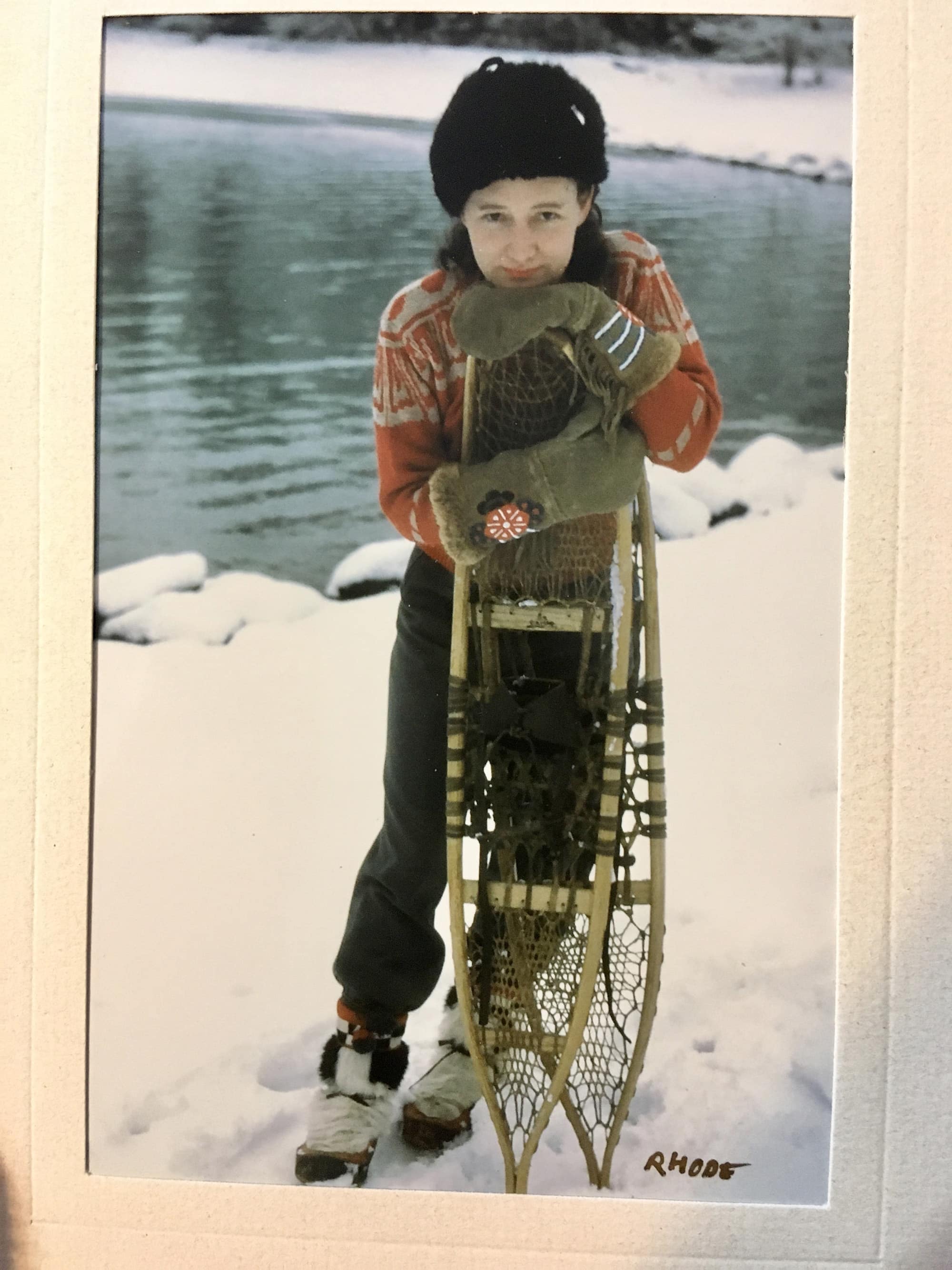

Helen Rhode

Helen was also working at Boeing. They met and were married in 1946. In an early 1990s article for We Alaskans, Doug O’Harra describes the Rhodes’ move to Cecil’s Cooper Landing cabin later in the same year they were wed: “They flew to Anchorage, boarded a train for Seward, got off at Moose Pass, and found a ride to the cabin. Helen says she remembers that Cecil walked straight into the kitchen and unrolled the dried remains of his sourdough starter, wrapped in wax paper. It was still potent after four years. A few days later, they ate sourdough pancakes for breakfast.”

Many years before, Cecil had studied film at the University of Michigan, and upon his return to Alaska he set about producing a wildlife film. He and Helen invested in film-making equipment, and he backpacked right out of their lakeside home and into the Kenai Mountains for days seeking just the right images. Three years later, his first film was complete, and the Rhodes traveled out-of-state to promote it.

Over the next 30 years, he produced a half-dozen independent films as well as footage for Disney and National Geographic studios. Also during this time, according to O’Harra’s article, Helen began accompanying Cecil on his wilderness excursions. Cecil gave her a German-made Exakta camera, and she began making still images of the same subjects he was filming.

In the 1960s, Helen bought a Leica that she used for the rest of her life. With her camera, she produced photographs that appeared in newspapers, books and magazines, and on postcards and placemats.

Besides the wildlife imagery that the Rhodes brought to the world, they were heavily invested in their community. Cecil helped with local elections and conservation issues, while Helen was involved with the Cooper Landing Community Club, the local school and planning commission, the Dall Homemakers, and the local gun club. She also helped with trash clean-ups, and was known as Cooper Landing’s leading booster.

We Alaskans article

In the Aug. 10, 1967, edition of the Seward Phoenix-Log, Margaret Branson wrote about a film presentation Cecil put on in Cooper Landing, projecting his movie on a sheet hung on the wall at the home of Jack Randall. She called Cecil “modest and self-effacing” but claimed that these qualities “must be part of his charm and his success with his audiences.”

After Cecil died in December 1979, an effort was launched to change the name of what was then known as Cooper Mountain to Cecil Rhode Mountain, and (although few maps show this yet) six years after Helen’s death in September 1992, a similar effort in her honor produced similar results.

Now, if hikers pause atop Cecil Rhode Mountain and look just south of due west across the narrow Cooper Creek drainage, they can eyeball a 3,947-foot peak called Helen Rhode Mountain in the Cooper Mountain massif.

Still side by side, after all these years.

Enjoy these articles? Sign up for our monthly newsletter to be sure to see them or follow us on Facebook or Instagram. Sign up below!

Clark Fair, a lifetime Alaskan now living in Homer, grew up on a homestead in the Soldotna area. He is a former high school English teacher and journalist who now does freelance writing and photography and works part time for Kenai Peninsula College.

Clark Fair, a lifetime Alaskan now living in Homer, grew up on a homestead in the Soldotna area. He is a former high school English teacher and journalist who now does freelance writing and photography and works part time for Kenai Peninsula College.