By Clark Fair

By the time Harry A. Johnson heard the handcar moving toward him down the rails, he had walked 15 of the 20 miles to Seward from his mining camp on Victory Creek. Earlier in the day, he had been attacked by a brown bear, and now, using a shovel for a cane, he was working his way toward town to get some stitches for the nine bite wounds on his arms, legs and back.

Harry A. Johnson (far right) with a party of hunters, 1904. From Mary Barry’s Seward, Alaska: A History of the Gateway City, Vol. III, p216.

Manually propelling the handcar were Johnson’s friends, Fred Beyer and Mat Schlosser, who applied the brakes and rolled to a stop alongside him. According to Johnson’s own account of the event, published in the 1961-62 edition of the Alaska Hunting and Fishing Guide, their conversation was brief:

“What happened to you?”

“Never mind. Get going to Seward and the doctor.”

And they did. Down the rails they traveled, dropping off their friend at the Hotel Sexton before calling on Dr. John Baughman, who came and “sewed up” Johnson’s wounds. By the time The Seward Gateway newspaper reported the incident five days later, on July 25, 1908, Johnson was recuperating at the Coleman House and said he was “feeling pretty well, though stiff and sore.”

Johnson, who was born in 1874 and was trained as a blacksmith, had come to Alaska from Erie, Pennsylvania, in 1904, to work for the Alaska Central Railway as a meat hunter. He and a crew of “mountain hunters” were employed to supply wild game—mostly moose and Dall sheep—for the tables of the men laying track north from Seward.

Over the next 60 years in Alaska, Johnson also subsistence hunted and trapped, prospected for gold, performed other seasonal work for the railroad, was a longshoreman in Seward, worked as a hunting guide in the Kenai Mountains, and became a renowned wildlife photographer, toting his treasured Graflex Speed Graphic camera with him almost everywhere he went.

Johnson’s trapline cabin. (Hope & Sunrise Historical Society, Harry A. Johnson Collection 2010.048.095.)

Hope historian Diane Olthuis, who wrote about Johnson in Goldpan, Trapline & Camera, described him as “small and wiry,” perhaps 5-foot-6 and 120 pounds, with dark hair and a handsome face that featured a lean nose and high cheekbones. She said he was known widely as a fastidious man, who wasted nothing, spoke only when he had something worth saying, had gentlemanly manners, and was unbelievably tough.

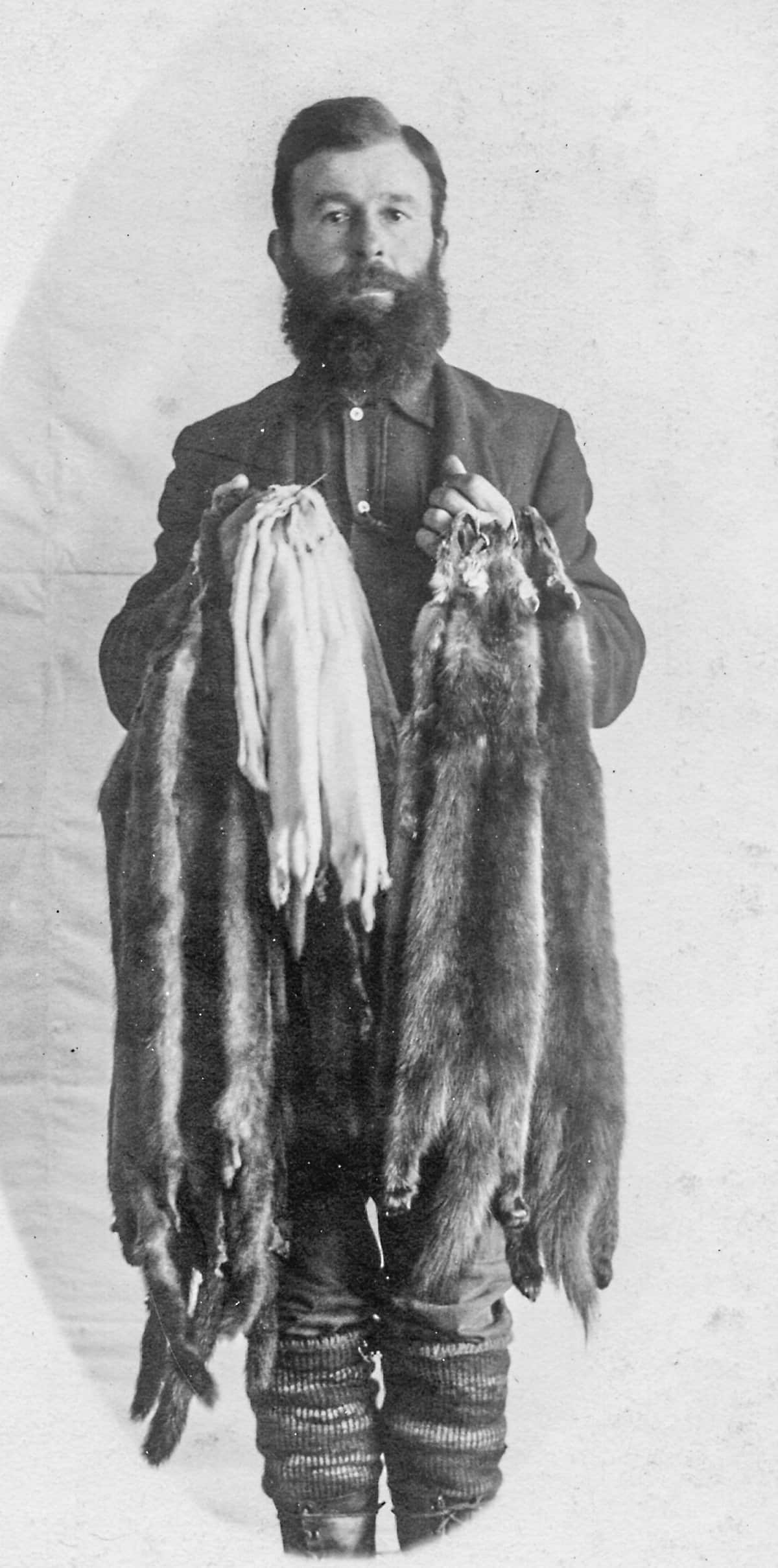

Harry A. Johnson and Furs

(Hope & Sunrise Historical Society: Harry A. Johnson Collection 2010.048.031)

According U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service historian, Gary Titus, Johnson was one of only 10 residents of Moose Pass in 1920, and the following year he constructed a cabin near Resurrection Creek, 18 miles south of Hope, and moved there. Although he built a home in Moose Pass in 1948, he returned to his mountain cabin and his traplines there until well into his 80s.

But on the afternoon of July 20, 1908, Johnson was a gold miner exploring a knoll high in the countryside when he was startled by the sight of twin brown bear cubs lying in a patch of alders only about 25 feet away. The appearance of cubs, Johnson knew from experience, almost always meant a sow was nearby.

“I stand perfectly still and give the surroundings a careful, close scrutiny which yields no adult bear,” he wrote. “Where is the mother grizzly? I am sure she is somewhere on the knoll.”

He considered his situation: He was alone and unarmed. In one hand he held a shovel. The pack on his back held a prospector’s pick and a gold pan.

Suddenly, the sow materialized before him, immediately focusing on Johnson with her eyes wide and her nose wrinkling in alarm. A moment later she charged, and Johnson yelled, “Get back! Get back!” But she kept coming.

Johnson swung his shovel and struck the sow on the side of the head. She, on the other hand, swung a paw and cuffed Johnson on the side of his chest. As he went down, she stood over him, then bounded around him and growled before biting him five times.

“She suddenly left me and galloped up toward where the cubs were, squealing and growling all the time,” he wrote. “(Then) she came back again, still growling, and bit me four more times. Perhaps 30 seconds have passed since the bear came in sight, but she has been in continuous, fast action, and I am completely at her mercy.”

It was at this point, as the bear romped away again, Johnson said, that some part of his mind noticed that the sow’s breath smelled of berries.

He didn’t dwell long on the fragrance. Instead, he lay as still as possible, awaiting what he presumed was going to be a death blow from the agitated bear. But the sow did not return, and eventually he rose cautiously and headed back for camp.

“The bear didn’t shake me and didn’t inflict tearing bites,” Johnson wrote. “In the whole battle I received only one serious bite. The shock of it, however, stayed with me for years.”

Fortunately for Johnson, the shock was not enough to fog his common sense. After walking for an hour just to reach his camp at Victory Creek, he examined his wounds and decided that a doctor’s needle and thread were going to be required. A few hours later, he was on the handcart with Beyer and Schlosser, rolling noisily toward Seward.

Johnson’s main cabin near Resurrection Creek.

Johnson did not allow the mauling to prevent him from returning to the mountains. For nearly 30 years, he lived alone in the cabin he had built in 1921. From there, he ran an extensive trapline, hiking into town in the spring to sell furs and buy provisions for another year in the mountains. In 1926, southwest of his home, he constructed a trapline cabin that in 2000 was included in the National Register of Historic Places.

Harry A. Johnson’s Black Smith Tent (Hope & Sunrise Historical Society’s Harry A. Johnson Collection 2010.048.026)

Olthuis reported that Johnson, who had only one working lung—perhaps due to a childhood illness— guided his last hunter in 1955, at the age of 80. He is said to have climbed a tree at age 85, and at age 86 to have made one final 23-mile hike in to his mountain cabin.

But in 1961, his body would no longer cooperate and he finally had to seek assistance. He asked John Kinda to take him on horseback to the mountain cabin, where Kinda said that Johnson “bawled like a baby,” knowing he would never see the place again.

In 1962, he sold the cabin to Cooper Landing guide Max Hamilton, and in 1963—55 years after he had struggled wounded from the mountains to get a ride into town—two neighbors gave Johnson another, final ride to Seward, to the Wesleyan Nursing Home.

He died on the morning of June 14, 1965, at age 90, in the Pioneer Wing of the Seward Hospital. And, as Olthuis said in her book, “An Alaskan era passed with him.”

Enjoy these articles? Sign up for our monthly newsletter to be sure to see them or follow us on Facebook or Instagram. Sign up below!

Clark Fair, a lifetime Alaskan now living in Homer, grew up on a homestead in the Soldotna area. He is a former high school English teacher and journalist who now does freelance writing and photography and works part time for Kenai Peninsula College.

Clark Fair, a lifetime Alaskan now living in Homer, grew up on a homestead in the Soldotna area. He is a former high school English teacher and journalist who now does freelance writing and photography and works part time for Kenai Peninsula College.